News of News - The Fifth Power

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

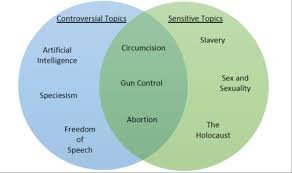

Recently, a gesture made by Elon Musk during a rally has sparked widespread social debate about whether it resembled a Nazi salute. Many left-wing commentators speculated that Musk deliberately used this gesture to show support for Nazism, and CNN analyzed the incident on its program. Meanwhile, right-wing commentators refuted the suspicions and accusations made by the left.

In this article, we acknowledge the right of all individuals and media to express their views on this matter. However, we aim to provide an analysis of this incident to offer readers a different perspective on the issue. Our focus is: Using Behavioral Analysis to Identify “Bad Actors” and Its Parallels with Stasi Practices.

1. Behavioral Analysis and Freedom of Expression

It’s entirely within the rights of individuals or media to analyze or question the actions of public figures, especially when these actions are connected to sensitive historical contexts. However, such analyses should be grounded in facts and rationality, rather than preconceived biases or political agendas.

2. The Risk of Behavioral Surveillance: A Stasi Parallel

Behavioral analysis, if taken too far, can resemble the practices of the Stasi (East German secret police), who scrutinized every action and word of citizens to identify “potential threats.” Modern society faces similar risks when social media behavior and gestures are overanalyzed:

- Over-interpretation: Innocuous gestures or words may be exaggerated into intentional signals.

- Intent Assumption: Inferring someone’s intent based solely on behavior can lead to unfair accusations.

- Public Pressure: Individuals subjected to such scrutiny often find it difficult to defend themselves fairly.

3. Complexity of Symbols and History

The Nazi salute is a historically sensitive symbol tied to immense societal trauma. It’s understandable that any gesture resembling it would spark concern or outrage. However, it’s important to distinguish between deliberate mimicry and unintentional resemblance:

- Public figures like Elon Musk do bear greater responsibility to avoid ambiguous gestures.

- Without concrete evidence of intent, there’s a danger of turning scrutiny into baseless accusations.

4. Media’s Role

Media outlets like CNN have the right to analyze such controversies but also bear a responsibility to present balanced perspectives rather than inflaming division or amplifying speculation.

5. Conclusion

Using behavioral analysis to identify “bad actors” can sometimes verge on modern-day Stasi-like practices, fostering unnecessary societal tensions. Regarding Elon Musk’s gesture, the following points are crucial:

- Encourage rational, fact-based discussions over emotional or politically charged reactions.

- Avoid jumping to conclusions about intent without evidence.

- Balance the public’s right to critique with a fair and measured approach to interpretation.

In a modern society sensitive to historical trauma and symbolism, caution and fairness are essential to prevent the escalation of misunderstanding into social division.

In this article, we do not aim to support or oppose any side. Our purpose is to caution everyone: using behavioral analysis to identify “bad actors” is a Stasi-style method of social control. While every individual has the full right to evaluate and analyze, citizens’ behavior should not be subject to such scrutiny and examination. When a society begins to rely on behavioral analysis to find “bad actors,” it has already started down the path of a Stasi model. This model, commonly employed in the Soviet Union, Eastern Europe, and other socialist states to prevent subversion, represents a form of societal governance that must be avoided at all costs.

Many people often refer to dictatorship and totalitarianism, but do they truly understand the differences between these two concepts? Let’s explain.

In both dictatorship and totalitarianism, the people don’t get to choose their leaders, and power is taken by force or control. In a dictatorship, one person or a small group holds all the power and makes decisions without letting the people have a say. Although they control the government, people might still have some freedom in their personal lives, as long as they don’t speak out against the leader.

Totalitarianism, on the other hand, takes control much further. The government doesn’t just run the country; it controls almost every part of people’s lives—where they work, what they believe, and even what they say or think. In both systems, freedom is taken away, but totalitarianism is much more extreme, trying to control everything. Neither system is good for the people because they’re forced to live under these rules without any choice.

An important difference between the two is whether the system tolerates “wrong” ideas. In a dictatorship, as long as people don’t challenge the leader, their thoughts don’t matter much. But in totalitarianism, people are forced to believe the “correct” ideas in every part of life. If you hold an incorrect idea, you are cancelled. Totalitarianism often starts with good intentions—the belief that if everyone thinks the right way, society will become perfect. But politics is not like science, where there’s always a clear right or wrong answer. It’s more like negotiation, where people’s needs differ, and the goal is to find a balance, like buyers and sellers agreeing on a price.

Another important thing to understand is that just because a leader is tough or even a bad person doesn’t mean they are—or want to be—a dictator. Similarly, just because a leader is gentle or seems like a good person doesn’t mean they will promote freedom and democracy. Throughout history, we’ve seen many leaders with good ideas and intentions accidentally lead to totalitarianism. In fact, good people with good intentions are sometimes more likely to pursue totalitarianism. They get upset when bad things happen in society and want a complete solution to stop all of it. But in trying to create a “perfect” world, they can end up taking away people’s freedoms, forcing them to think and act in certain ways to avoid bad things.

Freedom of speech depends on freedom of thought. If people aren’t allowed to think freely—even if their ideas are “wrong”—how can they speak freely? And without that, how can they be part of a democracy? Free thinking is even more important than free speech, and holding ideas that others might consider “incorrect” is a fundamental human right. These ideas should be debated, not canceled. People have the right to share their thoughts, even if others disagree, and just like in a marketplace, the value of these ideas will be decided over time.